A recent study by University of Georgia Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, funded by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Coastal Resources Division, sheds light on the economic contributions of saltwater recreational fishing to Georgia’s coastal economy.

Saltwater recreational fishing is a popular activity that draws anglers to Georgia’s coastal water bodies, including its tidal creeks, sounds and open ocean. This industry encompasses a diverse group of amateur anglers and enthusiasts who cast their lines from personal boats and docks, public beaches and piers.

The study, led by UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant’s Coastal Economist Eugene Frimpong, found that in 2022, over a quarter of a million recreational anglers spent $223.7 million on saltwater fishing activities in Georgia. These activities include purchasing fishing tackle, such as fishing rods, lines, and lures, while also incurring additional expenses related to transportation and food.

According to Frimpong, money spent on saltwater recreational fishing circulates through Georgia’s economy, creating a multiplier effect where every dollar spent can have a significant impact as it moves across different sectors. Results of the study show that saltwater recreational fishing trips in Georgia supported 3,217 full-time or part-time jobs and contributed $310.6 million in sales in 2022.

“The study reveals the significant economic contribution of this particular sector to Georgia’s coastal economy,” says Frimpong. “It also provides the state with baseline socioeconomic information to inform management practices that support the economic viability of saltwater recreational fishing and the overall health of our coastal resources.”

According to Carolyn Belcher, marine fisheries section chief at Georgia DNR’s Coastal Resources Division, most fishery management decisions are informed by the health of a fish population, which is determined through stock assessment models. Implementing fishing seasons as well size and catch limits are ways to maintain healthy populations.

“The effects of these actions are easy to assess on the fish because of the availability of fishery-dependent data sources; however, without socioeconomic information like the data provided by this UGA study, it is difficult to assess how proposed management will affect the people involved in the fishery,” says Belcher.

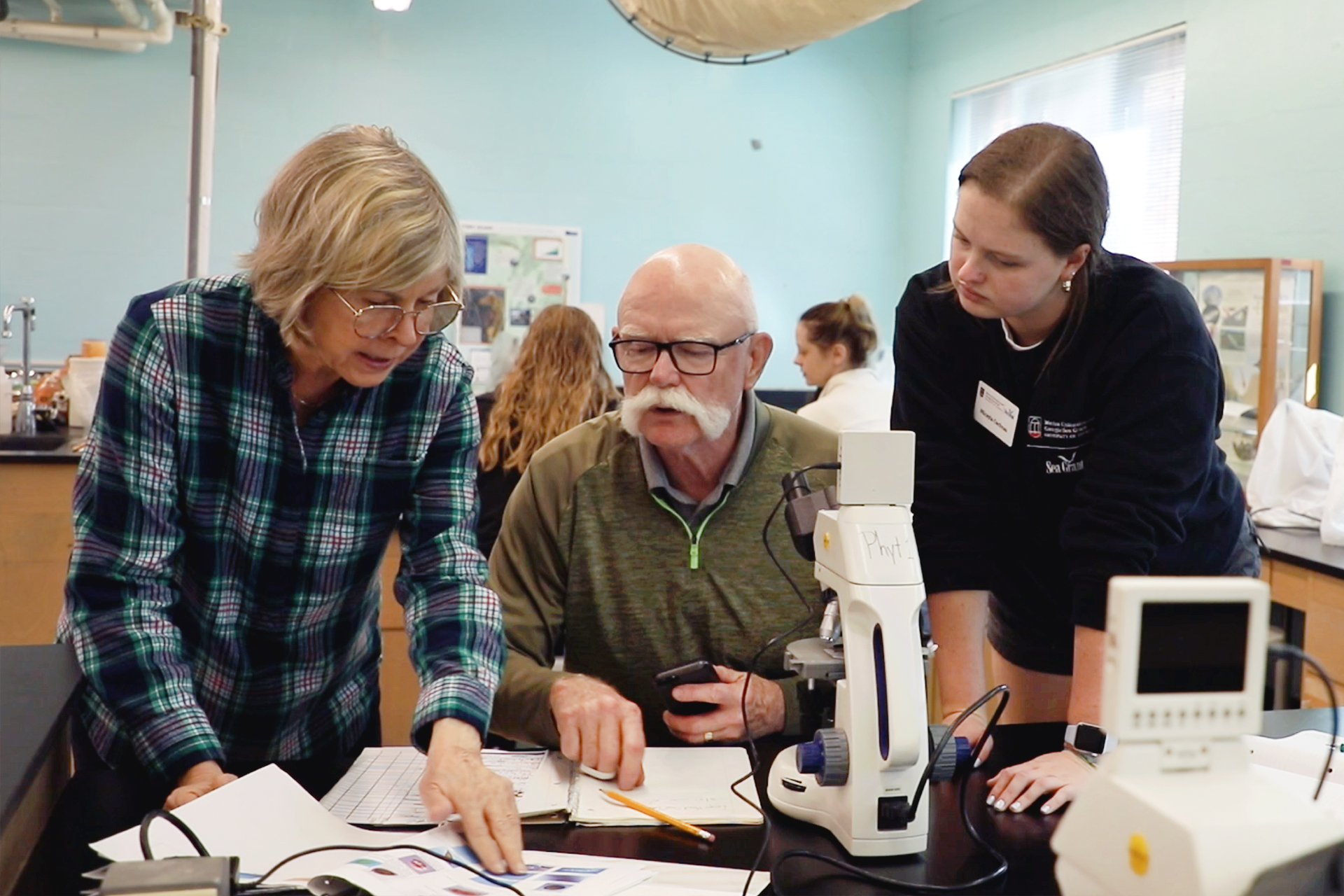

Frimpong gathered information for the study through a state-wide survey of recreational anglers. In addition to collecting expenditure data, the survey included demographic and geographic questions to gain insight into who engages in saltwater recreational fishing and where anglers fish.

“Knowing the most popular destinations for recreational fishing and whether people are fishing by boat or from a pier helps us determine who and where to target educational resources and programs that help protect and conserve our fisheries resources,” says Bryan Fluech, associate director of extension at UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant.

UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant’s Guide to Coastal Fishing in Georgia map series feature a map of the inshore coastal waters within each county as well as tips on responsible harvesting practices. Knowing, through the study, that Glynn, Chatham and Camden counties are the top three fishing destinations in coastal Georgia enables extension professionals to make sure tackle shops and marinas in these counties are stocked with the guides and other resources.

This information will also allow UGA staff to target specific counties and sites with outreach programs, like Trawl to Trash, which is designed to educate boaters and beachgoers about the impacts of marine debris and encourage use of recycled trawl bags to collect and remove debris from Georgia’s waterways.

“Trawl to Trash was launched with recreational anglers in mind, realizing they often need a way to collect and store debris while on the water,” says Fluech. “Knowing that most recreational fishing is happening by boat or from shore validates our efforts to target outreach efforts at marinas and public access points.”

Georgia’s saltwater recreational fishing sector is intricately linked with multiple industries, including retail, manufacturing, hospitality and tourism. It not only generates government revenue through taxes and fees but also plays a crucial role in supporting conservation efforts. The economic significance and cultural popularity of the industry underscores the importance of adopting sustainable practices and effective management to ensure the industry’s sustainable growth and success in Georgia.

Writer: Emily Kenworthy, ekenworthy@uga.edu, 336-466-1520

Contact: Eugene Frimpong, eugene.frimpong@uga.edu, 912-262-2379

“We Know Georgia” showcases how UGA is using its expertise and resources to spur economic prosperity across the state and uphold its commitment to serve Georgia. We are sharing stories of resiliency, entrepreneurship, sustainability and economic prosperity to show how UGA works with communities to make life better for Georgians. Learn more here.