Seven students from universities across Georgia have been selected to participate in the year-long Georgia Sea Grant Research Trainee program. The students will work with faculty and professional mentors to conduct marine research and gain new professional skills.

Research conducted by the trainees will address one or more of Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant’s four focus areas: healthy coastal ecosystems, sustainable fisheries and aquaculture, resilient communities and economies, and environmental literacy and workforce development.

“By pairing students with academic and professional mentors, and immersing them in interdisciplinary research experiences, Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant is helping prepare a diverse workforce for jobs in the future,” says Mona Behl, associate director of Georgia Sea Grant.

The trainees will design research projects that build on their dissertations or theses while connecting with extension and education specialists at Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant who will help share their work with coastal communities. Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant is a UGA Public Service unit.

Samantha Alvey

Samantha Alvey is a master’s student in biology at Georgia Southern University. As part of her traineeship, she will be studying antibiotic resistance in coastal waters.

Bacteria are able to develop resistance to antibiotics and enter streams and rivers through wastewater discharge and runoff. These bacteria accumulate on river sediments where recreational activities, like fishing and boating, re-release the bacteria into the water where they can cause disease. Alvey will collect water and measure how the amount of antibiotic resistance bacteria changes when sediment is disturbed by human recreation. She will also examine the potential for the resistant bacteria to spread from rivers to the coast, which will be useful to inform water policy aimed at reducing ecological and public health risks.

“This program not only provides essential resources to support my research but also opportunities to communicate my findings to my peers and the public through conferences and public outreach events that I might not otherwise have access to during my graduate program,” Alvey said.

Courtney Balling

Courtney Balling, a Ph.D. student in the departments of Integrative Conservation and Geography at UGA, is researching the environmental drivers of septic system failure.

Coastal areas are especially at risk of septic system failure in the coming decades due to sea level rise and changes in rainfall patterns. Balling will look at how environmental conditions, like tidal fluctuation and precipitation, impact bacterial concentrations in groundwater near residential septic systems. This research will be shared with officials working in public health, wastewater, and planning to help create sustainable wastewater solutions for the future.

“I would love to be a part of an extension service. I truly enjoy research and community engagement, and extension would allow for both. This traineeship is allowing me to gather more of the skills I’ll need for that kind of work—everything from grant writing and research design to strategic communication and community partnership,” Balling said.

Jennifer Dorick

Jennifer Dorick is a Ph.D. student at UGA studying food science with a focus on food safety. Her project will focus on food safety hazards in aquaponics, a sustainable agricultural practice that integrates aquaculture and hydroponic farming.

Dorick will study a commercial aquaponics system, looking at what pathogens, like E.coli and salmonella enterica, are present and where they are most prevalent within the system. This research will provide more insight into foodborne pathogen risks in the aquaponics industry and will provide valuable information to other commercial aquaponics farms that could prevent the introduction of these pathogens in their systems.

“The traineeship will contribute to my research goals by funding a research field that is creating an innovative and sustainable method to produce fresh food sources to urban, rural, and food desert areas in Georgia,” Dorick said.

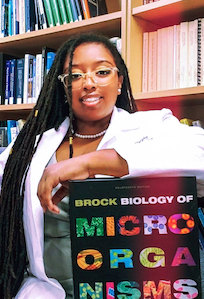

Monét Murphy

Monét Murphy is an undergraduate student pursuing a double major in marine science and environmental science at Savannah State University. Her project will involve studying benthic foraminifera in the Savannah River Estuary. Benthic foraminifera are tiny, single-celled organisms that can serve as bioindicators of environmental conditions in marine environments, including natural variability and human impacts. They are generally well preserved in the fossil record.

As part of her project, Murphy will study foraminifera distribution and abundance in samples collected before, during and after the deepening of the Savannah River harbor. This research will determine if the upstream extension of saline waters due to Savannah harbor deepening has impacted foraminifera distribution and if these changes have the potential to be impacted in the sediment record.

“The traineeship program will help me better communicate my results, the importance of benthic foraminifera, and the impacts of harbor deepening to stakeholders and how the study of the fossil record informs us of the range of past climatic, coastal and oceanographic conditions,” Murphy said.

Alexandra Muscalus

Alexandra Muscalus is a Ph.D. student in the Ocean Science and Engineering program at Georgia Tech. Her research focuses on hydrodynamics and coastal impacts of the wake generated by container ships, which pose public safety hazards and have been linked to rapid shoreline erosion along shipping channels.

Muscalus will study sites in the Savannah River to measure the wave characteristics and energy of ship wake in the main shipping channel as well as nearby secondary channels. Her research will be beneficial in providing new information for coastal managers when it comes to mitigating impacts of low-frequency wakes on shorelines.

“The traineeship will allow me to conclude my thesis work in a way that transforms my previous findings into meaningful and actionable results for stakeholders. At the same time, it will provide a means for me to interact with stakeholder groups and help me decide in which specific direction I would like to take my career,” Muscalus said.

Sarah Roney

Sarah Roney is a Ph.D. student in the Ocean Science and Engineering program at Georgia Tech. Her traineeship will involve researching how different types of organic compounds identified from predator waste products can improve how oysters defend themselves against predation.

Working with researchers at the UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant Shellfish Research Lab, Roney will introduce two organic compounds in a hatchery system that have been shown to induce defensive responses in oysters. The goal is to produce a stronger, well-defended oyster that can increase the success of restored reefs and living shorelines as well as the productivity of farmed oysters, enhancing oyster restoration practices as well as oyster mariculture efforts.

“With the trainee program, I can work with not only my academic and scientific advisor, Marc Weissburg, but also the director of UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant’s Shellfish Research Lab, Tom Bliss, learning about the ins-and-outs of the shellfish industry in Georgia and the ways scientific research can be beneficial and applicable to the trade,” Roney said.

Megan Tomamichel

Megan Tomamichel is a Ph.D. student at UGA’s Odum School of Ecology researching black gill disease in shrimp. Her project involves developing a stock assessment model of shrimp populations that incorporates black gill transmission and harvesting strategies under ongoing oceanic warming.

The model will account for the impacts of black gill on shrimp, and it can be used to inform management strategies for shrimp harvest under changing environmental conditions.

“I was interested in applying to the Georgia Sea Grant Research Trainee program to support my current research addressing a disease of concern in Georgia fisheries. This program aligns with my goals to use science as a tool to help support the people and ecosystems of the Georgia Coast,” Tomamichel said.