Anytime you take a dip in the ocean, you can expect to be swimming among hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of microscopic organisms called phytoplankton. They come in different shapes and sizes, and all play a critical role in the marine ecosystem, serving as the base of the marine food web and providing at least half the Earth’s oxygen.

In a balanced ecosystem, phytoplankton provide food for a wide range of marine life; however, when too many nutrients are available, some may grow out of control and form harmful algal blooms (HABs) that affect fish, shellfish, mammals, birds and even people.

“As nutrients and pollutants are making their way to the coast, monitoring harmful algal blooms is increasingly important,” says Katie Higgins, volunteer coordinator and marine educator at UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant.

To help monitor the potential for harmful blooms, a UGA team including Higgins and Natalie Cohen, assistant professor at UGA Skidaway Institute of Oceanography was formed. They are collaborating to better track and understand HAB events along the coast as part of a research project funded by SECOORA, the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association.

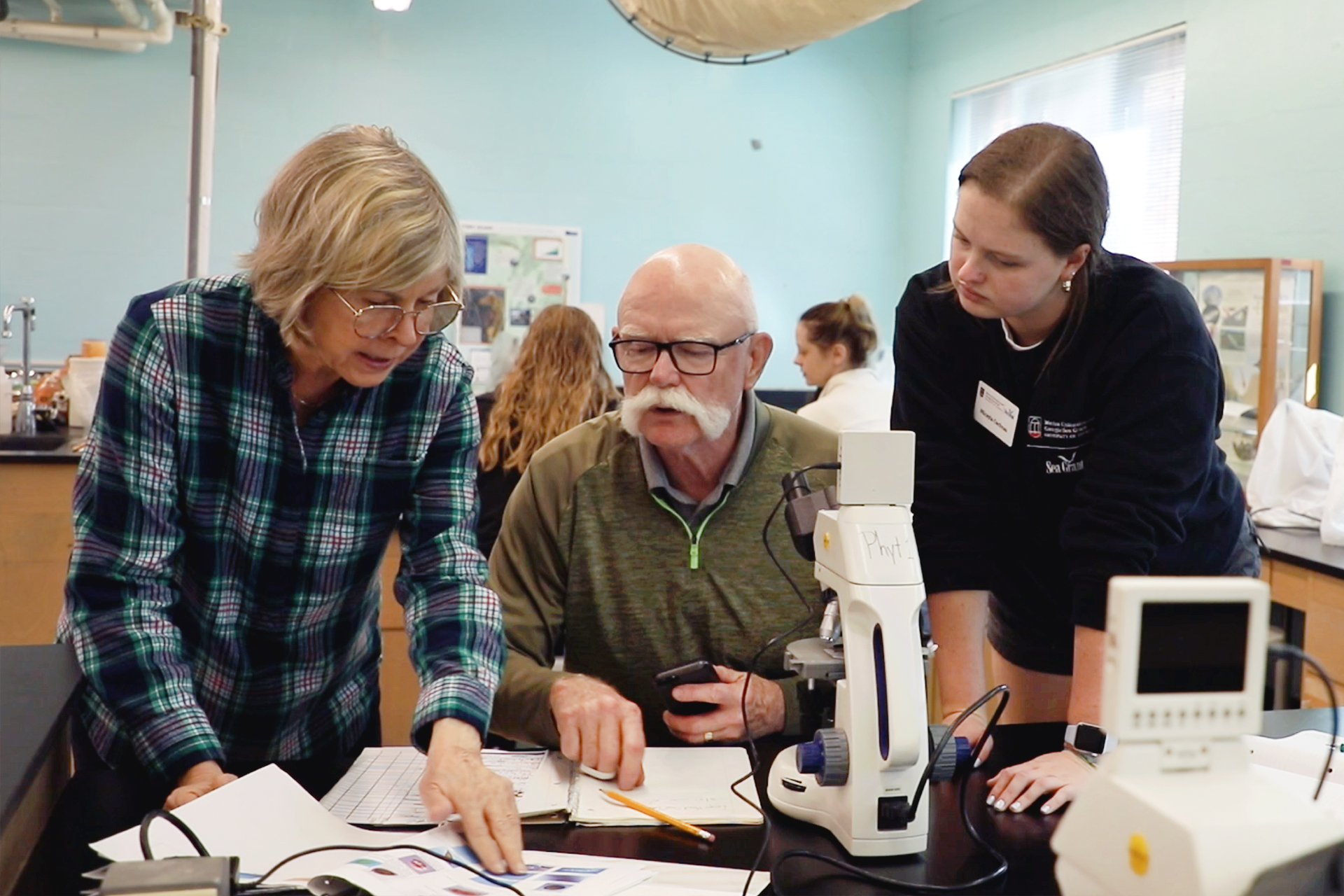

“Currently, the only HABs monitoring in Georgia is done through NOAA’s Phytoplankton Monitoring Network (PMN),” says Higgins, who coordinates a team of UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant volunteers who have participated in the network for 20 years by monitoring a site on the Skidaway River behind the UGA Aquarium. Every Thursday, volunteers collect water samples from the river and process them in the lab at the aquarium, counting and observing the abundance the phytoplankton in each sample before submitting the information to NOAA.

Back in 2017, their monitoring efforts helped researchers at UGA Skidaway Institute document a bloom of Akashiwo sanguinea, a type of phytoplankton considered to be a harmful algal species. The bloom coincided with a massive die-off of oyster larvae in UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant’s Shellfish Research Lab, located next door to the sampling site. At the time, researchers hypothesized that this species of algae was to blame. It produces a sticky substance that has killed birds during blooms on the west coast by damaging the water proofing on their feathers.

“The event in the Skidaway River demonstrated that [HABs] have the potential to happen here and could cause harm to local aquaculture,” says Cohen. She is working with Mallory Mintz, a master’s student at UGA, to build on the PMN volunteer monitoring efforts by collecting weekly data on cell densities of HAB species over a two-year period and incorporating more water quality parameters into the sampling effort.

By collecting quantitative cell count data and measuring oxygen, pH and salinity at the sampling site, the team can start to better understand environmental drivers that are conducive to HAB formation in Georgia estuaries, specifically Akashiwo.

“This is sort of the first step in coming up with a forecasting plan. We really have to figure out environmental parameters that are most important, and later we can predict when blooms are likely to occur,” says Cohen.

While volunteer observations have suggested a seasonality to the abundance of Akashiwo in the Skidaway River, through this more robust monitoring effort, the research team was able, for the first time, to quantify Akashiwo presence over an entire year and correlate this with water quality parameters.

“Starting in late July, Akashiwo cell counts went from undetectable to a max of 150 cells per milliliter, reaching bloom level,” says Cohen.

“We hope that through this season and next summer, we’ll see if there are patterns over time.”

The ultimate goal is to establish a regional notification network to communicate with local residents and aquaculture organizations in coastal Georgia about HABs. All the water quality and cell count data obtained through the project will be made publicly accessible so that others will be able to explore the data.

“These UGA and volunteer efforts will promote awareness and establish connections between scientists, shellfish farmers, and residents interested in the seasonal timing of blooms and the potential for HAB events to become more frequent in Georgia,” says Higgins.